The forgetting curve

New post

When we first learn something, it doesn't take long for us to completely forget it. This is an experience that we all have. When we learned something new in school, it wasn't long before we forgot it. In primary school, when there is less information to learn, we sometimes only studied for a test on the last day and successfully completed the task the next day. But when someone asked us about this topic the following week, we only had fragments of knowledge left, and taking the exam was a distant memory. When they increased the workload in school, we saw that there was no longer enough time in one day to learn everything that was the subject of our knowledge test. At that point we learned that we would need to review the material. If we then crossed the threshold of the university, we quickly realized that daily repetition and learning new material became an almost impossible task. If we prepare for an exam for a month, finding a way to keep that knowledge until the end of the month is a huge challenge. What we do then is that we significantly increase the number of hours we spend studying per day. We get the feeling that even eight or ten-hour days of learning are no longer enough, as we have to cover some new material while repeating everything we have learned until that day. Many of us almost give up.

But German psychologist Herman Ebbinghaus discovered the key to the solution of how we can spend only a few hours of learning per day and retain knowledge until the exam that will take place months later. He discovered the so-called forgetting curve, based on spaced repetition. In his research, he noticed that when we first learn something, we only remember it for a short time. But when we repeat that information, something interesting happens. We would expect that we would forget the material at the same rate, but this is not the case.

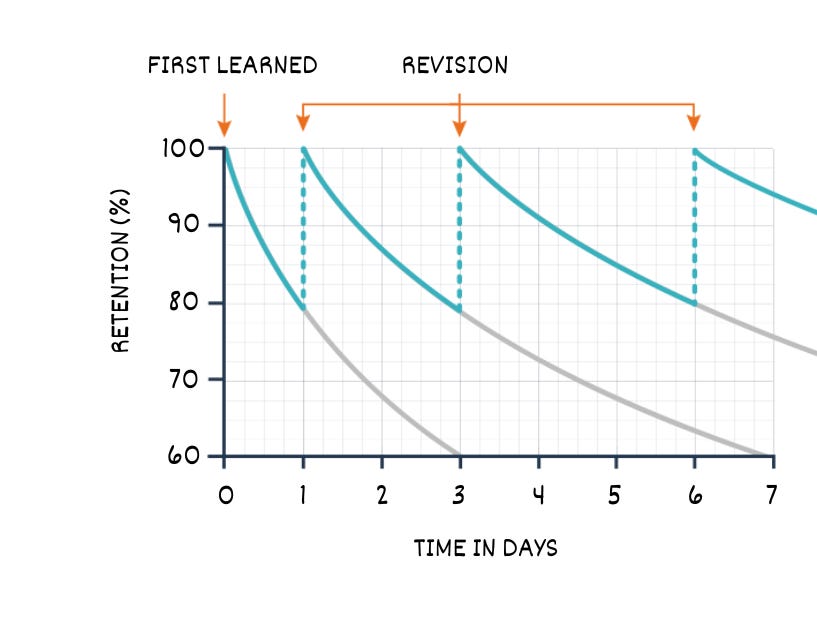

If we look at the graph above, we see that forgetting occurs at a certain rate. Looking at the forgetting curve when we first learn something, it is quite steep and drops quickly. The gray part of the line represents the decline of the curve if we don't repeat the data. After one day, we remember only 80% of what we learned. After three days, only 60%, etc. When the memory drops below 80%, the data is already quite difficult to recall, and we notice significant gaps in our knowledge. We want to review the material just before that happens, just before we would have to re-learn large parts of the subject at hand. This is what we often discovered ourselves, and therefore repeated the material almost every day. But it turns out that this is not necessary. If we look at the graph above again, we see that our knowledge is restored to 100% with each repetition, but that is not the crucial part of Ebbinghaus's discovery. The key is that we forget the material more slowly with each repetition. So after the first repetition, we see that the curve is already a little flatter, indicating a slower decline in memory. After the second repetition, the curve is even flatter, and so on. Therefore, we can increase the time between repetitions, which means that we do not need to repeat the material every day, but with increasingly larger intervals between repetitions. When we repeat the material many times, it becomes so ingrained in our memory that we essentially never forget it.

In practice, this means that when we learn something for the first time, we need to repeat the information after one day. After the first repetition, we should repeat it again after a few days. When we repeat it for the second time, the time until the next repetition is already more than a week.

So our dear Ebbinghaus has shown us that we don't need to repeat the material on a daily basis. This is actually a waste of time. Suddenly, we realize that 2 or 3 hours of studying a day are enough, and there is enough time for new material and reviewing old material. If we want to apply this principle ourselves, we don't need a calendar to measure the time between repetitions. Instead, we can use the Anki app, which combines active recall and spaced repetition in a monstrously powerful combination that allows us to spend less time studying, achieve better grades, and retain knowledge for a long time, even after the exam is long over.